What is Real?

It's easy to prove that imagination makes things real—pick up a book and read.

What is it that makes something real in our minds? For an adult, many things are intangible, yet they are powerfully real. So it is for children. But how long does magic last for a young child?

When do we stop blurring fantasy and reality?1 When do we stop believing everything we hear?

The clues come to us from the context in which we hear information. That includes culture where social connections do sway us.2

Below, I have a lovely story to illustrate our transition into adulthood.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth ideas, information, and interviews on the value of culture.

Become a supporter and access new series, topic break-downs in The Vault.

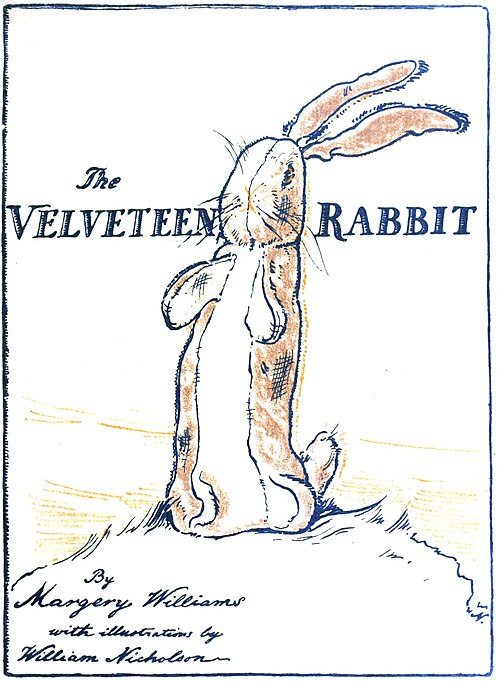

On a Christmas morning, a little Boy receives many presents. Among them is a Velveteen Rabbit.

“There was once a velveteen rabbit, and in the beginning he was really splendid. He was fat and bunchy, as a rabbit should be; his coat was spotted brown and white, he had real thread whiskers, and his ears were lined with pink sateen.”

At first he doesn’t notice it, but with time Rabbit finds a place in little Boy’s heart. Rabbit snuggles with him at night, and plays with him during the day.

But Rabbit knows he’s not Real, he’s wearing out, and one fateful day little Boy becomes ill with scarlet fever3 and the Rabbit has to be burned… that’s the story’s premise in The Velveteen Rabbit.4

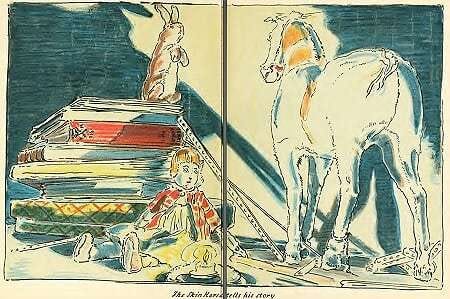

“What is REAL?” Asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you’re made,” said the Skin Horse.5 “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” Asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?”

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of. Your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don't matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

Who can say where dream ends and reality begins?

There’s a second Real.

Bianco’s greatest insight, the one that made The Velveteen Rabbit a genuinely philosophical work—reveals the true task of growing up, which lies not in simple self-actualization but in careful negotiation of the delicate transition from one order of reality to another.

Central to the transition is the limiting of the imagination to more indirect spheres of experience—dreams, literature, art—in exchange for an independent, more plastic sense of self.

But the process, by necessity, will begin with tragedy. Just as the Velveteen Rabbit comes to believe he will be Real forever, he is thrown out.

“Of what use was it to be loved and lose one’s beauty and become Real if it all ended like this?” the heartbroken rabbit wonders. A tear drops from his eye and out steps the beautiful fairy who promises to make him Real.

“Wasn’t I Real before?” the little rabbit asks. “You were Real to the Boy,” the fairy gently replies, “because he loved you. Now you shall be Real to every one.”

The fairy takes the rabbit to the forest, where the wild rabbits live, and gives the velveteen rabbit a kiss. Instantly he is changed into a real rabbit, although it takes a long time for him to realize this.

“He actually had hind legs! He gave one leap, and the joy of using those hind legs was so great, that he went springing about the turf.

He was a Real Rabbit at last!”

The mission of fantasy, far from belying truth,” wrote Bianco, “is often to present truth in an understandable form.” In the story, the remedy for being without the Boy for the Rabbit is to live outside his imagination and to explore the wilderness and mystery of life.

Growth and change come with the awareness of the impermanence of things. However, we can (and should) dip into our imagination often through reading.

To Think Different, Read Different

Take the most subscribed 'Substacks' on culture: they feel like a version of the same popular topics.

But is that stuff of value, things you can actually use? Which begs the question—is there a good way of knowing things you can use? I’ve been asking myself this question more frequently as I dip in an out of essays and books. [read more]

In case you were wondering, the answer is between approximately 2 and 3 years of age. That’s when we begin to understand the logical connection between ideas—the ‘why’ of things—which is the reason 2-3 year olds start to ask ‘Why?’ about almost everything. By age 4, we can use the context in which the new information is presented to determine whether or not it’s real consistently.

It’s sobering to look at the data of how few adults think with their own heads. Culture does indeed dictate the degree of independence vs. sheeple behavior.

The vaccine for scarlet fever was only discovered in 1924, two years after the first publication of Velveteen. Then in 1940, the vaccine was eclipsed by the discovery of penicillin. So, the burning of the toys in 1922 was a sensible order from the doctor.

A British children’s book written by Margery Williams Bianco. It chronicles the story of a stuffed Rabbit’s desire to become real through the love of his owner. The story was first published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1921 featuring illustrations from Williams' daughter, Pamela Bianco. It was published as a book in 1922 and has been republished many times since.

The Skin Horse is the wisest and oldest toy in the nursery, the boy’s uncle owned it.