The Language that Never Dies

And the 650,000 Italian soldiers who said 'no' after September 8, 1943.

It would be easy to abandon Latin to the old heap of history. After all, it’s not a current language. Why should we keep learning something we don’t use enough?

It would also be foolish to do so. I speak from the experience of reading Latin for six years as part of my education—what it teaches in discipline and depth of thought is unequaled in other languages.

Which is also the reason why Latin represents the pinnacle of legal writing worldwide, used to state and define facts, situations and commitments.

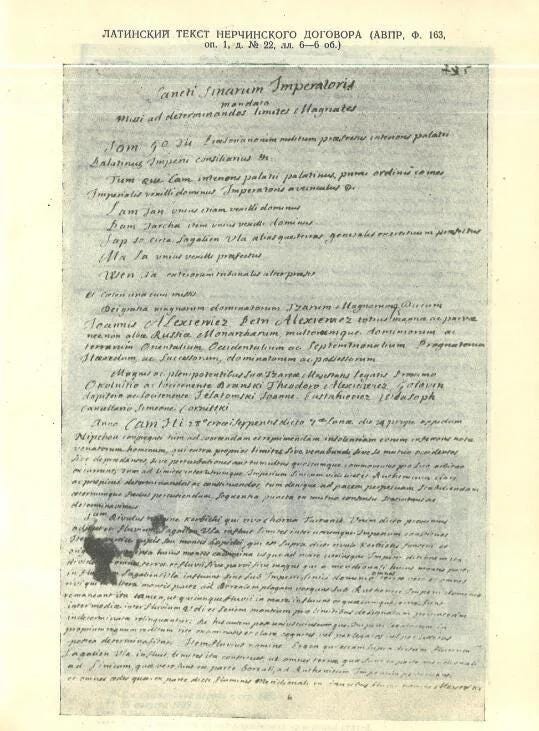

Few people know that the official documents signed with the Treaty of Nerčinsk between China and Russia on 27 August 1689 were not written in Russian, nor in Chinese, nor in German or English, but in Latin.

According to an international custom on the interpretation of treaties, later accepted and recognized in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969, the official language of the treaty is of great importance in the interpretation because it prevails in the event that there are differences between the versions drawn up in other languages.

Cicero, who accused Catiline of having plotted a coup d’état, went down in history for having uttered four simple words: “Quo usque tandem abutere,” or “To what extent will you abuse?”

Writer Giovanni Guareschi1 zeroed into the value of Latin to this day.

“Latin is a precise, essential language.

It will be abandoned not because it is inadequate to the new demands of progress, but because the new men will no longer be adequate to it.

When the era of demagogues and charlatans begins, a language like Latin will no longer be useful and any boor will be able to hold a public speech with impunity and speak in such a way as not to be kicked off the platform.

And the secret will consist in the fact that he, using an approximate, elusive and pleasantly ‘sounding’ phrasebook, will be able to speak for an hour without saying anything. Something impossible with Latin.”

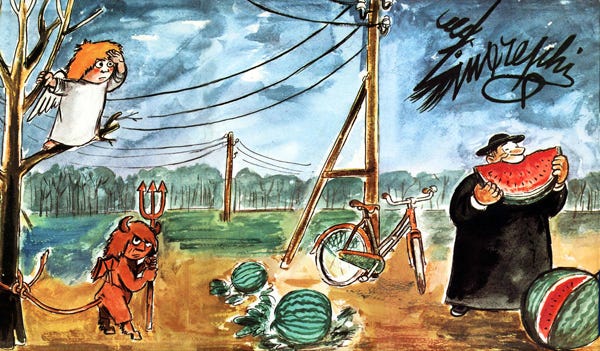

A prolific author, Second Lieutenant Giovannino Guareschi conceived his most popular characters in the camps. Don Camillo, Peppone and Candido were born in the concentration camps after 1943.

More than 650,000 Italian military internees were imprisoned for saying ‘no’ to Nazi-fascism after September 8 of that year. Giovannino Guareschi was among them. Those who chose to carry out an ‘unarmed resistance’ to the bitter end had to endure dramatic human and psychological conditions.

Second Lieutenant Giovannino Guareschi was captured in Alessandria on September 9, 1943, and interned in Bremervoerde-Sandostel, Czestokowa, Beniaminovo, Wietzendorf. He fought his ‘good fight’ for twenty months.

Because the legal status of prisoners of war was not recognized, along with the removal of rights to protection, health, and dignity, Italian soldiers were used as a workforce in grueling shifts and the most demanding tasks for the Third Reich war machine.

Approximately 50 thousand died as a result of hunger, cold and violence punctuated by forced labor, the frequent transfers, and the continuous aerial bombardments of factories and annexed labor camps.

On the other hand, the ever-living hope, religiosity, faith, culture, and the collective life were fundamental for survival. The human spirit soared beyond selfishness and misunderstandings generated by the Reich’s organization and discipline.

Enduring friendships arose from the miserable conditions. Guareschi forged bonds with musician and composer Arturo Coppola, actor Gianrico Tedeschi, designer Giuseppe Novello, poet Roberto Rebora, philosopher Enzo Paci, and many others.

Emblematic of that time was Guareschi’s reflection that

“We did not live like brutes: we built ourselves, with nothing, the ‘Democratic City’. A ‘City’ built by everyone, defended by everyone, because the internee made ‘a continuous choice’ in the Lager, which lasted twenty months, stressful and unique in the historiography of mass imprisonment.”

Claudio Sommaruga, Il dovere della Memoria

The reduction to a number, marked on a tag to always carry on the person, was one of the particular elements of the ‘inhabitants’ of the lagers who maintained their dignity, denying their political, military and civil support to Nazi-fascism.

The glue that holds all of our Relationships together

Some time ago I worked with a company to help build a narrative to diminish turnover and create lasting impact. It’s the kind of work I love to do—help a team and company flourish.

The humor in Guareschi’s later publications and writings was hatched here and made him the moral leader of the internees. Its sharpness was a weapon towards the adversary, but always respectful of human value and steeped into Christian values.

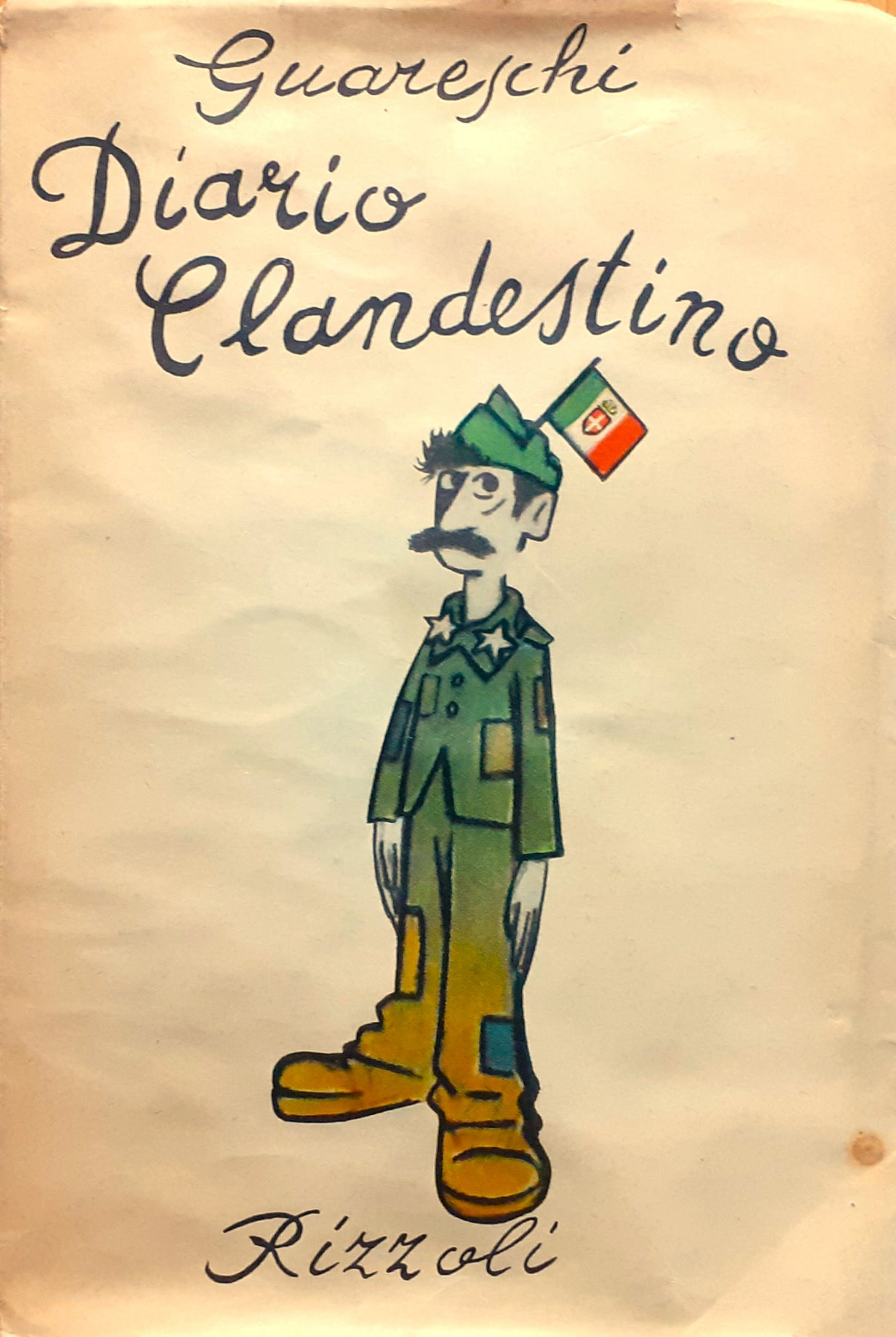

He published his 1943-1945 clandestine Diary in 1949. A small volume dedicated “to the comrades who did not return,” the diary was reprinted many times.

Guareschi recognized in Latin a fusion of language and thought. Its value reminds us of the literary and philosophical legacy we draw from Dante to Shakespeare, Calderon de la Barca to Montaigne, Pascal, Thomas Stearns Eliot.

If we can imagine the golden bough with which Aeneas descended to Hades, which is nothing other than the mistletoe in which the arboreal spirit of the Norse god Balder is enclosed, we owe it to the words that wove those tales.

If Juliet and Romeo are the modern names of Pyramus and Thisbe—who in the East are Layla and Maynun—if the falling of leaves is equated, for everyone, over the centuries with life that dies (via Homer, Semonides, Mimnermus, Seneca, Arnault, Leopardi, Giacosa, Tyutchev, Ungaretti), the emotion that unites us in the crumbs of our time passes through words.

Conversing with the millennia, checking on the horizontal map where the rivers of the hypothesized Indo-European common mother have flowed, Latin proposes itself as a thread in the labyrinth and—while we possess it—the value of humanitas without borders.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth ideas, information, and interviews on the value of culture.

Become a supporter and access new series, topic break-downs in The Vault.

Giovannino Oliviero Giuseppe Guareschi was an Italian journalist, cartoonist, and humorist whose best known creation is the priest Don Camillo. The first, short story featuring the violent priest who speaks with Jesus, destined to rival Peppone, the communist mayor of his town, dates back to 1946.

His books are the second most translated fiction books in the world. With 311 translations (including Hebrew, Korean, Japanese, and Swahili), he follows The Little Prince, which has been translated into over 600 languages, and is ahead of Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio, which boasts 261 translations.