Pilgrimage

A long journey of purpose and moral significance.

I was a pilgrim at the end of April last year when I journeyed from Bari to Brindisi and Lecce to reach Santa Maria di Leuca, a destination that had personal importance to me. Since 2019, Leuca is also a very special place for pilgrims.

I’d like to use the word ‘pilgrim’ in the broader meaning of ‘person who travels’ in search of meaning. Something that has become ever so rare in contemporary culture. Pilgrimage has cultural value.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extras—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

Given the geography and history of Italy, it’s possible to come across pilgrimage routes nearly everywhere. Perhaps that’s why energy and connection are so strong throughout the country.

There’s the Via Degli Dei, a 130 km route pilgrims took to cross the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines. This cultural trail crosses a series of mountains that take their names from ancient deities: Adonis, Venus and Jupiter.

From the 7th to the 4th century BC the Etruscans were the first to travel part of the route. In 189 BC, the Romans founded the first colony (Bononia). And it’s from Bologna that the path goes through woods, paths and ancient thousand-year-old roads. A special ‘passport’ certifies passage, la Credenziale.

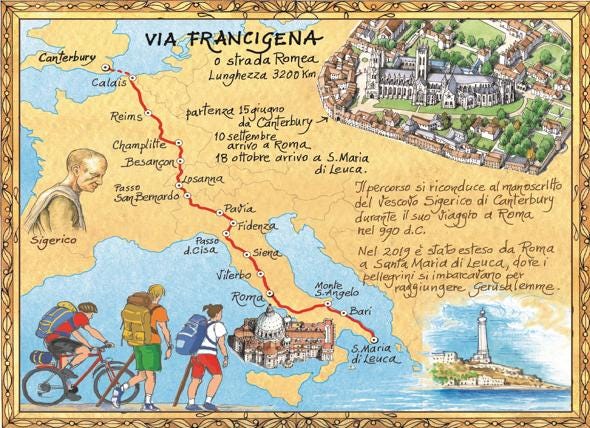

But there’s another ancient path that crosses five different countries in Europe and the length of Italy—Via Francigena. 3200 km go from Canterbury to Rome, then onward to Santa Maria di Leuca, the very tip of the heel in Puglia (added in 2019.)

While in Brindisi (an important port city for the Crusades), we met a writer who was walking parts of the southern path to detail guides for travelers. In San Quirico D’Orcia (province of Siena), we crossed paths with a couple of friends who planned to walk five miles on the path locally.

It was her birthday, she explained, and the walk was a wish of a newly empty-nester to share conversation and reflection. They figured five miles immersed in nature was just the tonic they both needed.

Via Francigena was an important road and pilgrimage route for those wishing to visit the Holy See and the tombs of the apostles Peter and Paul in medieval times. The path was actually several possible routes that changed over the centuries.

We tend to associate the past with dark, backward times. It could be because of the Plague(s) that halved populations. But it wasn’t the only thing going on. In fact, many innovation driven by purpose and moral significance started in the Middle Ages.

[Related to Middle Ages]

Love: the Most Fundamental Market Principle

You’ll forgive the Franciscan for owning only one tunic. Clothing was a sign of wealth in Italy’s flourishing economy of the 13th Century. Even expensive vellum manuscripts were frowned upon. Books were alright, but purely as tools for learning. Though it was alright to give gifts to the monastery.

These people knew the power of transformation through travel in nature. The ‘holy’ bit comes from Old English halig, which means ‘bringing health.’ A physical path with a clear destination can free us to take in the views we encounter, smell the flowers, liberate our inner self.

To become a pilgrim was the act of ‘going out,’ leave the known and venture into the unknown. A conscious act of stepping out of the ordinary, a deliberate move away from the comfort zones we’ve built.

From the Middle Ages onward pilgrimage1 has changed little. The idea is to share stories, meals, or the simple act of walking together with strangers, people from different walks of life. Flexibility is a characteristic of pilgrimage.

Some days may feel more like a long journey’s into night,2 disruptive without the transformation. Humans have the gift of thought, but it can also become a burden if we don’t create the space to process our lives.

The purpose for my journey to Leuca was to find meaning in that special places, to say my goodbyes. What I got in addition to that was so much more—positive memories, rich encounters, kind hospitality, and all manners of cultural immersion.

Perhaps pilgrimage is an apt metaphor for life as it unites inner and outer experiences. Value is in the interaction of people and places.

Science’s word of the year in 1849 was spirit, in 2012 brain, certainty in 1850, uncertainty in 2019. Language is a signal in culture: we are experiencing a mid-world crisis.

That’s when Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales, about a group of 30 pilgrims who traveled to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket. The storytelling competition between pilgrims drawn from all ranks of society were part of my curriculum in English Literature and a humorous bit in one of my exams at Uni.

A reference to Eugene O’Neill 1940 autobiographical drama, Long Day’s Journey Into Night first published after the author’s death in 1956, as instructed. It was part of a course I took in American Literature at Uni, along with Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman and Tennessee William’s A Street Car Named Desire.