I’ve had a hard time motivating myself to write. Perhaps that’s the main reason why the last article on attention with links to essays and series fell a bit flat. I hit publish when the vibes had shifted toward fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD).

The shifts in media culture are also real. To the point that if we want to keep informed of what’s going on (without going insane with hype or propaganda manipulation) we need to turn to journalists who’ve put integrity and ethics back into the news.1

So I did what any self-respecting writer usually does, I curled up into a tight ball. It wasn’t to feel sorry for myself. After nearly twenty years of writing in public I’ve developed a sense of what’s not working. It was to focus on where from here.

Some of the changes I’ve made include the deletion of unnecessary distractions, i.e. a Facebook Page and Profile, a Twitter account that used to stream a blog, all DMs in/around social media. Algorithms encourage sameness and stoke FUD.

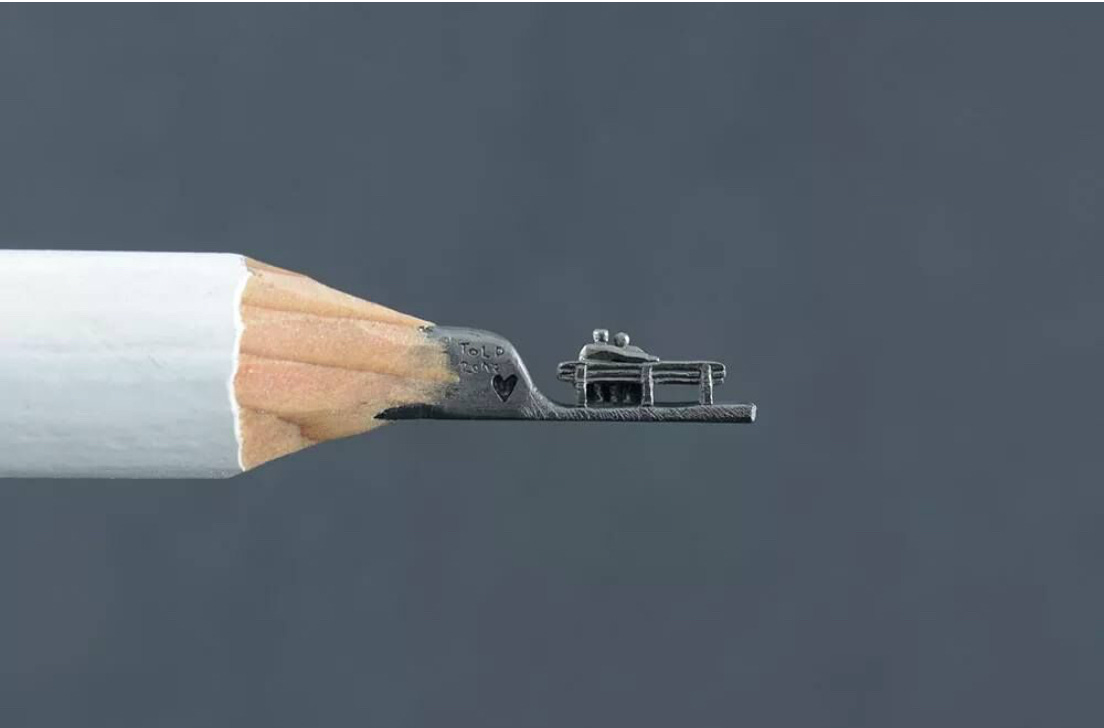

Focus to me means a deeper interest on the human conversation with reality. I came across a wonderful concept of a pencil sharpened to sit two lovers on a bench and it felt appropriate for what this space could become, its potential still untapped.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

I want to channel this concept—to sharpen the work, and focus more on the love and companionship on the bench part. The idea of value-aligned work came to me via Henrik Karlsson.

In a way, this work is akin to that of an art gallery, where I present exhibitions of ideas, concepts, and people to kick-start conversation. Anecdotally, much of the conversation happens elsewhere. But it would be nice to bring it here, too—for everyone’s benefit.

It was Henrik who might have suggested that a good idea for a book could be “how to handle being sentenced to freedom, and to handle it effectively, authentically, and responsibly.”2 I found this idea, liberating (no pun intended.)

I cannot think of a better collective project. It could start a better conversation with reality as so many have lost and are in danger of losing their access to it right now. We do need each other, none of us is coming out of this alive, etc. etc.

The concept belongs to the category of value-aligned work—when a group of people can agree on their needs and wants. From there, I thought that perhaps a better approach to On Value in Culture resembles more that I use with clients on retained assignments.

Where the process of doing the work is part of the assignment with loads of listening and observing. I came to this method to the scene, view the landscape, and craft the place we want to get to via what may seem messy behind-the scenes notes and steps. It’s a way to protect reflection and pauses, and preserve speed.

A mistake I’ve seen agencies and consultancies make is to get the ‘order,’ go away and build stuff, then present the final product/idea. The process is the part where we become, where we test and learn the most about each other, and about ourselves.

It’s counter intuitive, but humans have more speed in them when they can include depth in their work. So I think what value-aligned work may look like here is to include the process steps and stories with the insights.

I can give you an example of what that looks like (before insight) using part of a comment I made on an essay on the childhood of exceptional people, in which Henrik extracts the patterns and commonalities in education:

Exceptional people grow up in exceptional milieus

They had time to roam about and relied heavily on self-directed learning

They were heavily tutored 1-on-1

Cognitive apprenticeships (a favorite)

They were gifted children

Here’s the relevant part of the comment I made that highlights a process I learned intimately from direct exposure and experimentation (translations and interpreting are culture- and context-aware words to channel meaning):

“Related to subject matter of your essay here, I wanted to mention that in my early twenties I served as interpreter and translator to a center for the development of human potential with a focus on children.

The center was born out of a desire to treat children who had for some reason or other missed on their development. You may know them by their labels: cerebral palsy, autistic, Down Syndrome, etc.

They called them ‘brain-injured’ because no amount of physical therapy (the founder) had managed to make them better. Early on, this therapist partnered with a brain surgeon and started to document correlations between areas of the brain and lack of/incomplete output.

But then, the second part of the equation and answer to the question of how to make a child ‘well’ again was to figure out what ‘well’ looked like. To the surgery data, it was necessary to add developmental data. Hence a partnership with anthropologists to study human development ‘in the wild.’

Both data streams were rich with information.

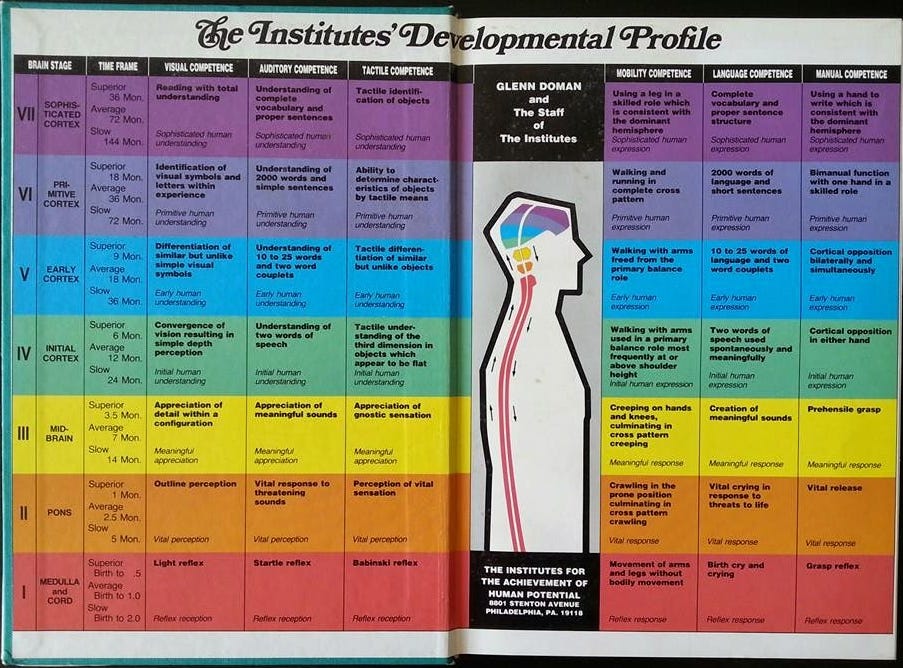

The question then became: how do we streamline it to the ‘minimum viable’ set of skills that lead to a regular development, given that our competencies are interconnected. This search for minimum viable led to a ‘developmental profile’ that documented how three main pathways into the brain (input) and seven different levels from birth to six years of age (and brain development phase) created the three main pathways of function in a human (output).

They called the result ‘Developmental Profile.’

To add nuance and turn the profile into a useful tool, the team worked on observing and documenting three ages per level: average, fast (your ‘genius’ level) and slow. Now they had an instrument that would allow them to evaluate a child’s competences (vision, auditory, tactile) and abilities (mobility, language, manual ability).

Clearly, the brain of children who had not developed normally had missed stages of input. Those cells in the brain were long gone. But, there are more cells sitting around that could possibly take on the job(s), if properly stimulated. The thing with catching up is that you have to increase frequency, intensity, and duration of the stimuli. Hence this time, the staff looked to a research center that works with human beings to stress-test capabilities for space missions: the AMES research center. Thus, ‘the program’ was born.

In 1964, riding on the wave of optimism in education (and life in general if you look at Italy, for example, but also many parts of the world), the therapist, Glenn Doman,3 had the idea of writing a book for parents titled, How to Teach Your Baby to Read.4 The book was meant as a tool for all parents—of what society deems average/regular children, and the others, too. He knew that when you grow one are of the brain, the whole brain grows. In other words, if you teach a child to read who cannot walk, his ability to move may also improve, as you’ve expanded capacity.

Heady concepts, but I’ve seen the results with my own eyes.

My cousin went on to play the piano, speak four languages and earn two doctoral degrees in education and psychology—her practice today is the gateway for psychologists to become accredited.

But also the dozens and dozens of other children who’ve improved in varying degrees through the program (itself a fairly brutal schedule and discipline that included nutrition, physical, and intellectual stimulation).

To this day, I buy a copy of How to Teach Your Baby to Read for new parents. Even if they do nothing, the book does such a good job of explaining the potential inherent in their babies that it influences changes in the environment in which they grow (floor, stimulation, etc.)

I didn’t want us to miss the physiological and physical aspects of environment or we’ll continue to educate the heads and atrophy the bodies. Perhaps this line of work suggests a more holistic path than athletics.

The interconnection of competencies and the building layers had tremendous appeal to me. I’ve since used the ‘Developmental Profile’ as forma mentis for other useful frameworks.

Doman used to say that every child at birth has the potential of Leonardo da Vinci. I’d like to believe that, as we’re desperate for new ideas that will put value back into culture.”

Value-aligned work develops over time based on continuous feedback loops and check-ins with reality. I could think that I write the best articles and essays, but if they lack an entry point from which I can overhear and observe what you want/use with them, they’re not as valuable to us as they could be.

I also think that this change will encourage a more direct and personal direction. Because I want to be in conversation with those of you who’ve already decided. Henrik put words in my head that express well:

“It is not that I’m some grumpy person who thinks that some people are great and others aren’t, in some predetermined way—I think you can to a large extent decide which kind you want to be. But if someone else isn’t measuring up, I have no idea how to convince them to do so. So I look for people who have already decided.”

The mutuality I mentioned in my last article.

If you made it all the way down here and don’t feel you wasted 7-10 minutes, consider giving this essay a ‘like.’ It helps others find it. And it makes me happy. If you have friend who would enjoy my essays, it is really helpful when you share it with them.

Coda

Alignment of wants and needs is also the thread that percolated throughout Last Tango in Halifax, a British comedy-drama series (BBC) I picked up a couple of weeks ago. Derek Jacobi, Anne Reid, Sarah Lancashire, and Nicola Walker are superb.

I’ve enjoyed the dialogue—which feels realistic and believable—the themes—late-life love and many of the challenges we face as we try to keep all things going around us.5 I like the honesty, bravery and lack of self-pity (Gillian/Walker), the levelheadedness and courage (Caroline/Lancashire), and the interaction of ordinary people (Alan/Jacobi) in relation to strong-willed women (especially Celia/Reid).

So, I recommend the show if you’re in the market for something interesting that can expand your horizons on the complexities of relationships.

I follow just two closely as of late, Jessica Yellin because of the level-headed and accessible reporting, and Dave Pell because sometimes he still manages to make me laugh (I do like the play on words.)

Henrik is from Sweden and lives in Denmark. I think that his cultural scene or melieu, as he describes it, is one reason that makes his thinking so appealing. The other, a bigger part, is his pursuit of continuous learning and use of conversation as a tool to advance concepts and ideas. (Long time readers may recognize this as one incarnation of my first blog, Conversation Agent.) A kindred spirit.

A short bio of a humble person with a joy for life and his work. I spent the better part of six years with his thoughts and stories in my head as I translated his writings and interpreted his talks and conferences. He was the first to congratulate me when I completed my doctoral degree and loved all children, it was clear from his work and actions.

Glenn Doman received his degree in physical therapy from the University of Pennsylvania in 1940. From that point on, he began pioneering the field of child brain development. In 1955, he founded The Institutes' world-renowned work with brain-injured children had led to vital discoveries regarding the growth and development of well children. The author has lived with, studied, and worked with children in more than one hundred nations, ranging from the most civilized to the most primitive. Doman lived to the age of 97.

The book has sold more than 13 million copies and it’s part of a series, for the parents who wish to have simple tools to deepen their child’s abilities and knowledge.

How To Teach Your Baby Math presents the simple steps for teaching mathematics through the development of thinking and reasoning skills. (The way we learned mathematics in school is in serious need of improvement.)

How to Give Your Baby Encyclopedic Knowledge shows how simple it is to develop a program that cultivates a young child’s awareness and understanding of the arts, science, and nature―to recognize the insects in the garden, to learn about the countries of the world, to discover the beauty of a Van Gogh painting, and much more.

How To Multiply Your Baby’s Intelligence provides a comprehensive program for teaching a young child how to read, understand mathematics, and multiply his/her overall learning potential in preparation for a lifetime of success.

How to Teach Your Baby to Be Physically Superb was designed to help maximize a child’s physical capabilities through each stage of mobility and shows how to create an environment that will enable her/him to more easily achieve that stage.

What to Do About Your Brain-Injured Child is for any parent / caretaker or professional who works with kids who have any of the diagnosis listed on the book or similar.

Sally Wainwright is the writer who puts dignity, humor and realism to the subject of an elderly couple in love. It never feels tacky or overdone. And I can see the ‘younger selves’ of both characters in the story. But there’s more. Both seniors have adult daughters and teenage grandsons, and life has not been particularly kind to either. It’s only 24 episodes, but a lot happens to all the characters.