If Airports Were More Like Libraries

Rather than gated commercial centers. Could we not make these 'in between' spaces into cultural hubs?

They’re some of the biggest hubs where people flow from different parts of the world. Hubs of privilege on one hand, because entry tickets are a large expense. Nets were hundreds of people work from different walks of life on the other.

Yet, with a few exceptions, airports all look alike. The sameness to how airports are structured serves a specific general purpose say mainstream opinion articles—to reduce stress, fear and disorientation, all factors that play a role in air travel.

Maybe the configuration and flows do the job.

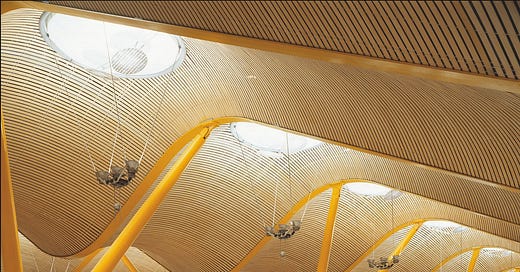

Some airport terminals do stand out for their beautiful architecture and use of lighting. So far, I’ve visited only a couple of those—the designs of both Madrid and Oslo have additional value in use.1

I’d say in general we dislike being stuck in an airport.

I’m reminded of various reactions to ‘The Terminal.’ Like ‘Cast Away,’ but in an airport. Spielberg’s film2 shows you can be just as alone in a crowd as you are by yourself. But it also speaks to strangers connecting across cultural barriers.

The most notable (as in pleasant) things that have happened to me at airports has been so far to cross path with interesting people. In one of our recent trips, I rubbed shoulders with Hugh Grant, actually.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

Grant must fly to get to places, like the rest of us. And he happened to board the train to the main hub for Terminal 5 in London right behind me. The doors nearly closed on his face. I think his stance was an attempt to transit under the radar.

I recognized him from the way he held his shoulders. Unlike the crowd that surged, I didn’t attempt a selfie. Incognito in regular clothes, Grant was a bigger hit than Chris Pine. We crossed paths with the ‘Nowhere Fast’ actor3 at the airport lounge on another occasion.

I caught his hair style and striped suit out of the corner of my eye after he got a plateful from the buffet. Pine was with a colleague (a guess). As I stood nearby, he debunked my impression that he was tall—funny how camera angles can skew reality.

Chance encounters

In a way, all our encounters at airports are by chance. We bump into people accidentally as we follow signs up escalators, or by design when we line up for boarding. It’s much nicer when there’s dialogue involved, rather than grunts.

My husband once crossed paths with Willem Dafoe.4 They had a satisfying conversation about rural Maine at the Portland Airport that nobody tried to interrupt.

Chance encounters are (almost) the point of travel. Because we have no agenda, random meetings hold the potential for magic.

Stress comes from other things, like the disassemble of oneself to get into the wait zone behind security. It’s now become normal to queue in line to enter the same environment, jacket/coat and shoes off, little transparent baggie with the essential toiletries (how is it that there are still loads of people who don’t know you’ve got to do that?) pass through a metal detector/body scan, hand over an identity document.

Concerts, conventions, fast trains (in Spain) all require those protocols. I still remember a simpler time, when that wasn’t the case. Part of the stress at airports is indeed what analyst Bruce Schneier defined ‘security theater.’

The Brits love theater, though their process is miserable: inefficient, chaotic, and often spiteful. I never thought I’d say this, Italy’s airports are a breeze in comparison. But there’s a larger reason why airports are stressful—one that doesn’t need to be so.

The chaos from the stores, the terrible-food court, and poor design—ambiguous signs, cattle shoots, super long escalators, poor connections between terminals, dark passages, out-of-order mobile walkways—pile on already tired humans.

Beauty is important to the humanistic worldview. We admire beautiful things. And the idea of beauty has changed with culture over time. It’s included nature and objects, along with people. Artists have made and recorded beauty over the centuries.

Given the connection we now have with travel, visionary architects have been brought in to work on airport expansions and new buildings. I’ve never been to Singapore, but if I had I would have enjoyed the integration of nature.

Apparently, along with nature and facilities to swim, there are also free cinemas open 24/7 and an entertainment deck with everything from the Xbox360 to Kinect stations. Most airports also have one or two bookstores.

However, those windowless shops are designed to maximize shelf space and drive purchases, not browsing. So they, too, become transactional spaces. A place to drop in, look around, and make eye contact with a human being only (and if) at the register.

Which is a shame, a missed opportunity for a different kind of contact. These spaces, the airports, are transitional. Their potential is much greater that mere utility. Any kind of travel—business or leisure—can become the portal to transformation.

The main thing that could aid in that direction is opportunity for relationships. To people, but also to space, and things—like access to art, nature, and knowledge in a calm environment.

Not here, not there, but definitely somewhere

Travel is not what it used to be. That’s both as in ‘not as bad,’ and also ‘not as pleasurable’ as it once was. I’ve witnessed many anti-social behaviors at an airport or on a flight. More so after the Covid pandemic. ‘Revenge’ ruined travel.

Crammed seats, fewer and far between services on planes may be part of the problem. But the experience in airports is an assault to the senses. The iper-efficient and iper-prepared mix with the defensive anxious and the harried last-minute travelers.

If we were to study airports as we do cities, using psychogeography, we’d look at the effect these spaces have on people’s emotions and behavior. English psychologist and researcher Steve Taylor has compared airport environments to what Celtic mythology calls ‘thin places.’5

Environments like woods or sacred forests are considered a sort of interregnum in which the boundaries between the material and spiritual dimensions become thin—spaces in which one is neither entirely in one place nor entirely in another.

Airports are more like liminal zones, places where boundaries fade. We’re not at home, and we’re not yet at our destination, but a space in between (Lat. limen), like a threshold, which could be interesting.

Thresholds are key elements of ritual design. When you go through a doorway, you step inside a new place. Rituals are highly symbolic experiences. They allow us to become someone different. Personal boundaries become fluid, and so does our sense of identity.

Flying is a threshold experience. But like for many businesses, little remains of the original magic. With the result that nobody ever marvels at the ability to be suspended in the sky between places anymore.

Making an investment in the space—a large entrance hall, but also the terminals, a piece of equipment—is a symbolic investment in an identity. We could be traveling with time or in the opposite direction through the airport experience as threshold.

“The perfect airport would be one where you would naturally be guided by the surroundings.”

Alejandro Puebla, senior airport planner, Jacobs

And while we’re focused on what’s next in our travels, we miss the possibility of what’s now.

But this idea of transformation, this opportunity to play with identity boundaries, to learn from observation or through conversation with others is wasted—because shopping areas are right there, ready to turn all this human potential and energy into consumption.6

“Those who have learned to walk on the threshold of the unknown worlds, by means of what are commonly termed par excellence the exact sciences, may then, with the fair white wings of imagination, hope to soar further into the unexplored amidst which we live.”

Ada Lovelace

Civility in captivity

Travelers may be the perfect consumer with time to kill, and so little in the way of choices. Once we clear security, our mood shifts. In the airport design business they refer to this moment as ‘the golden hour’—mostly with a ‘buy’ or screen interface.

Airports want to capitalize on it. Which is why so many don’t announce departure gates until 25 minutes to boarding. Is shopping-as-pacifier in captivity the best we can do? Have we come so far in civilization to buy more stuff we hardly need?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.