Prometheus

As the modern world confuses technology with knowledge, have we forgotten the Titan's gifts to humankind?

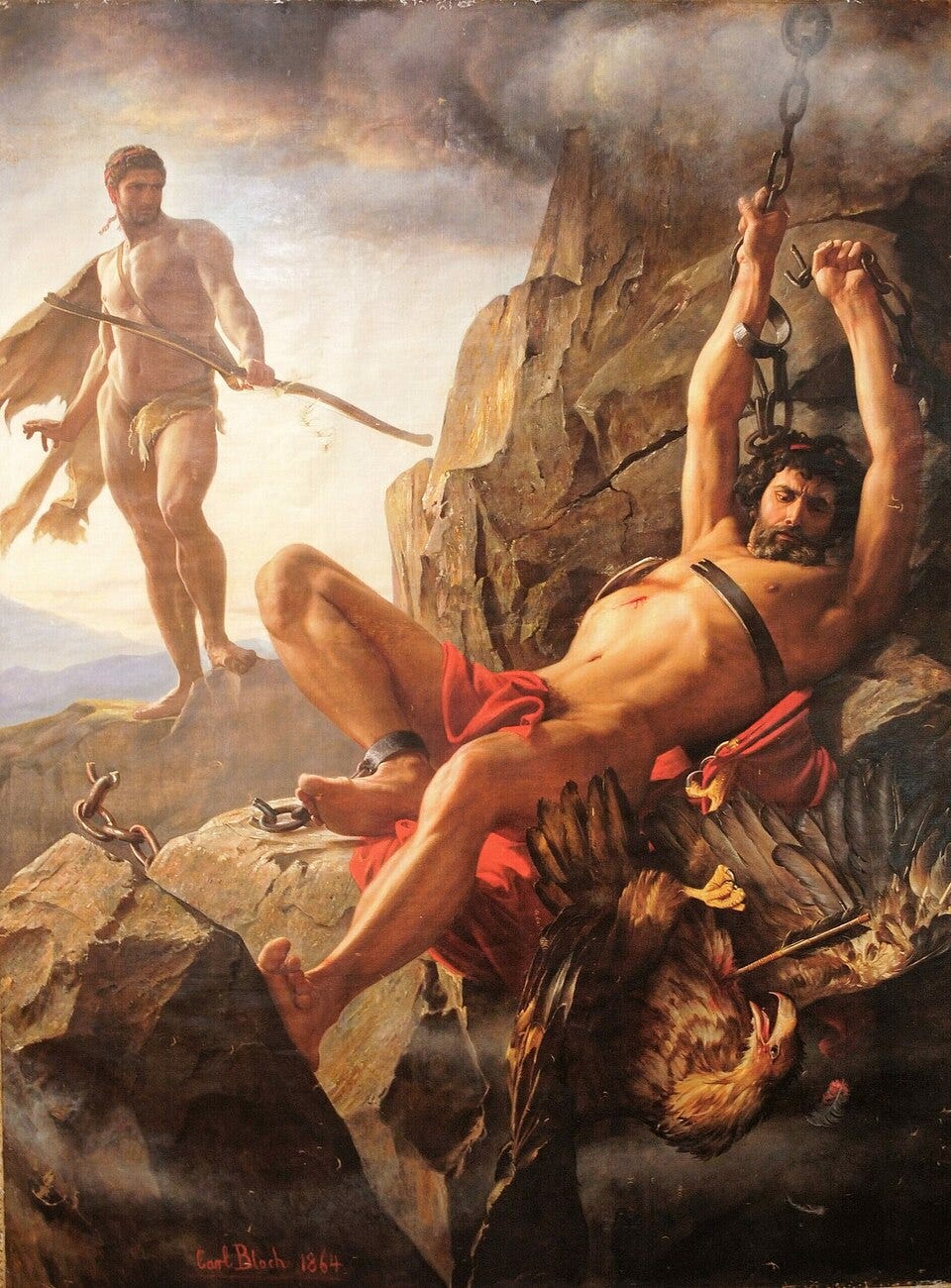

Son of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Clymene, the Titan’s name translates as ‘forethought,’1 which may indicate foresight and intelligence. Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humankind.

His intention was to give humans the means to create, innovate, and thrive—something that was province of the gods. By naming their projects ‘Prometheus’, some technology leaders aim to suggest their artificial computation does the same.

Of course, they forget two things.

One is that the consequences of Prometheus’ actions were severe. Zeus, who foresaw the effects of what he had done, condemned the Titan to eternal suffering—bound to a rock, an eagle feasting on his liver each day, only for it to regenerate overnight.

All follies come from the gods. Only love, the most irrational of human feelings, is generative. Creativity and innovation reside in the irrational. But development is based on reason, a system of rules governed by the principle of non-contradiction.

Development is not the same as progress. Because all things are multifaceted, reason cuts off meaning.

The second thing is that when Prometheus gave humankind techne (from Greek technê, doing), he transformed defenseless beings into masters of their own mind. In doing so, he made a promise he couldn’t keep—limitless life.

“He who doesn’t know his limits should fear fate.”

Aristotle

Zeus was correct in his punishment.

Today our ability to do has eclipsed our ability to foresee the effects of our doing. Technology unleashed tends to follow only protocol—and disregard what it sees as mere ‘resources.’ The tech age heralded a radical absence of meaning.

1/5

But first, a round of links. Since the last round-up which was a big hit, On Value in Culture published:

(🔒) A Theater of Envy—Rivalry, competition, and conflict laid bare: René Girard explains human desire through William Shakespeare’s plays.

unfold.

On the Line—To narrate is to put reality on a thread, so we can try and find direction.

(🔒) Metamorphosis—It’s still possible to reframe the linguistic perimeter that conceals the substance of things, and use it to steer change and direction.

The Art of the Interview—Conversation as a tool to make sense of the world. [Preface to a book I’ll be publishing here.]

(🔒) Elsa Morante, Writer as Creator of Ideas—Art holds us together, it’s the opposite of disintegration.

A Way Forward—On the value of the mother tongue to memory and the sense of self.

(🔒) What is Truth?—In an age where everything is representation, telling the truth has become a subversive act.

With many thanks to those who recommend and share this work of love. A reminder that some lengthy essays are free to all email subscribers, but then are archived in The Vault (🔒) online.

2/5

Technology tears us apart, says Nicholas Carr.

In a conversation with Jared Henderson, Carr talks about how the very the mechanisms that we thought useful for connection are actually damaging us. The concept works like this:

“This concept of the dissimilarity cascades, I think, is very important. Human beings have a bias to like people who they sense are similar to themselves and to dislike people who they sense are dissimilar to themselves. And what we assume is that the more we learn about somebody else, the more we’ll see how they’re like us and therefore the more we’ll like them.

While our instinct to like someone is strong, our instinct to dislike another person is actually slightly stronger. When you start getting more information about somebody, as soon as you see some way that they’re different from you, some way they’re unlike you, you start to put more and more emphasis on those differences. We begin to emphasize how they’re dissimilar to us.

We don’t disclose as much about ourselves all at once when we’re face to face with someone. In our in-person relationships we take more time and frequency to unfold as we’re not trying to fit into a (preset) category (to select) in a system.

The way social media sites are configured forces us to somehow fit ourselves into consumable content. This mechanism not only encourages us to manufacture what we say for optimal reception, but changes us in the process.

If you wanted to design a media system that would set off dissimilarity cascades, social media is kind of precisely what you design because it encourages people to disclose as much as possible as quickly as possible about themselves. We’re sort of these buzzing, blooming individuals, and if we present ourselves like that to others, they’re going to be overwhelmed and not know how to make sense of us.”

I’m glad Carr mentions Neil Postman’s thinking because his books were as early warning (especially Technopoly). And I talk about his work in my brief collection of essays (only on Kindle as my blog and most of my social media profiles are gone).

Because of my own early tech skepticism as I noticed the effects of social media on concentration and culture, I was among the first bloggers to write about his book The Shallows in 2011. The prescient book became a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize.

Not only has tech manipulated our attention and time, thus taking human energy away from our social lives, it’s also now taking energy resources to develop and maintain—both in enormous quantities.

With the recent AI developments in tech I think we’re playing with fire. Some of us grew up in the analog world and have learned to balance privacy with trust in relationships. Digital generations may not understand the value of this equilibrium.

3/5

Why don’t the wealthy build things of beauty anymore?

To me, there are two main reasons. One, unless one is surrounded by beautiful things, unless you’re educated to observe and connect with art and history, it’s hard to value beauty.

Two, a mind occupied by calculation hardly leaves room for taste, the province of humanistic education.

“Subconsciously, they prefer buildings which are aerodynamic and utilitarian. Materials are light: stone is replaced with glass. Ornamentation — seen as unnecessary baggage — is stripped off. Mass production is efficient, so it is fine if cities look the same.”

Ironically, in the quest for eternal life, they forget the value of timeless works.

“This preference for light materials stands in contrast to the patrons of the past, who lived in ‘eternal time’. The kings of old believed that their experiences, struggles, and hopes were part of a divine pattern which would recur until the end of days — and were thus of eternal relevance.”

They forget, because in the race to amass, they overlook the power of generating continuity. When we shift the focus of longevity from the individual to society, then our vision can and does build a lasting impact—duties along with privilege.

Instead, contemporary wealth burns on the ephemeral and transitory of the instant gratification.

4/5

To understand why so many adults are acting just like children, we shouldn’t blame Millennials, but look to Japan in the 1990s. I wrote about adultescence, but it looks like we might be in a Great Regression, back to kidults.

“By traditional standards, the rise of childish sensibilities represents dysfunction and danger, a rejection of autonomy, a mental illness or even a society-wide sickness.”

For example,

“In the 19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America (1835-40), described how despotism strives to keep subjects in ‘perpetual childhood’. At the turn of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud re-framed regression in psychological terms, defining it is as self-sabotage resulting from unresolved trauma.”

But there might be more to it than the various global crises we’re facing. Japan in the 1990s suggests that regression happens “when the youth and young adults of a hyper-connected post-industrial society lose faith in the future.”

When the Japanese economy that was going strong through the late ‘70s and ‘80s imploded, young people turned to culture.2 These behaviors could also “a form of experimentation and creative play.”3 A way to new forms of thinking and living.

“This was more than niche subculture. Throughout much of the 1990s, Japan’s most popular comic magazine, Weekly Shōnen Jump, sold 6 million copies a week. In 1995, a quarter-million attendees thronged the biggest fan convention, Comic Market, making it the largest fan gathering of any kind in the world.”

And now the kiddification of adults is everywhere in culture.

“Grownups pepper their online conversations with emoji and kidspeak, like ‘adulting’ and ‘besties’, sounding suspiciously like those pioneering Japanese schoolgirls of decades past. More adults read young-adult novels than the tweens and teens for whom they were ostensibly written. In Hollywood, sex scenes are out; heroes based on cartoon characters and toys dominate the box office. Hyperfans known as ‘stans’, whose lives revolve around their favorite celebrities, have roiled social media, the music industry and even US politics. The investment world has been hijacked by NFT cartoons of apes, while Christie’s auctions NFTs of kawaii characters called ‘fRiENDSiES’. At the literal end of the spectrum is ‘kidcore’, a retro aesthetic inspired by children’s clothing that is making inroads on fashion runways.”

Will these playful activities that create new ways of interacting with reality bring about change? Some believe that a regression to childhood is a form of reset—to the playfulness, creativity and diversity of our earlier selves. Others note that it also comes with temper tantrums.

But whether we transgress boundaries or police them through hate and violence, this regression signals a disappointment with the way things are going.

“Insecurity is what channels people of all ages into fantasies: some gentle, others dark and conspiratorial. Stuck indoors, crushed by loneliness, barraged by terrifying headlines 24/7, feeling abandoned by our political institutions, our only succor are the pacifiers of streaming entertainment and the dopamine drip of social media and ‘infotainment’. Our current moment can feel downright dystopian.”

Whatever the case, it remains to be seen whether kiddification is yet another form of manipulation and source of revenue, or a memory path to renewal. While we mull that over, I’d like to know what’s the definition of adult?

5/5

Rhetoricians can teach us to persuade through emotion. Lawyers can teach us to argue through law. Judges represent the law.

I’ve enjoyed watching actor Martin Shaw, who I’ve met as ‘Inspector George Gently’ grappling with inter-generational issues, in the robes of high court ‘Judge John Deed’ grappling with inter-personal relationships.

The BBC series is an intelligent narrative around current events and issues where English law interpretation takes center stage. BAFTA award-winning writer and producer GF Newman says, “The law itself is a major character in Judge John Deed.”

“A judge must have the courage to stand up for what is right, even in the face of adversity.”

Deed is the one high court judge who refuses to be bullied. Because he believes in the sanctity of the law, his stance is intellectual. In each series, there are legal and personal challenges—he does play with fire.

[sentencing the producer of a TV game show after a contestant has died]

“Celebrity. The pursuit of the talentless, by the mindless. It’s become a disease of the twenty-first century. It pollutes our society, and it diminishes all who seek it, and all who worship it. And you must bear some of the responsibility for foisting this empty nonsense onto a gullible public.”

It’s a drama that doesn’t patronize and makes one think. A rare occurrence these days.

Not everyone knows that Prometheus also stole a chest from the goddess Athena. The chest held two precious things, two things that allowed man to survive for thousands and thousands of years—Intelligence and Memory.

Intelligence, from intus (inside) and legere (to read), literally means ‘to read inside.’ Not outside, not beyond, but ‘inside.’ It means a person who has intelligence knows how to look at the heart of things, knows how to grasp their hidden aspects.

Prometheus, however, also gave people memory. With this myth, the ancient Greeks tell us something very important—that intelligence without memory has no value. We use memory to treasure past experiences, but it makes sense only we transmit it.

Like a flame, memory goes from house to house, from generation to generation. Aeneas carried his father Anchises on his shoulders to help him escape from Troy. The son of a mortal (Anchises was King Priam of Troy’s cousin) and the goddess of beauty (Aphrodite, Venus in Rome), apparently Aeneas chose to save a least useful thing—an old person.

But he did so because the elderly are the custodians of the memory of a people, our history (Aeneas is considered the progenitor of the Roman race). To understand the present, we must know the past. Memory’s like a light bulb turned on in a room that had remained dark until that moment.

However, the Greeks tell us that memory without intelligence is useless. It’s of no use to know that Socrates—the greatest philosopher of all time—was put to death by the Athenians. What matters is to understand why.

To evaluate the intelligence of a person we listen to the answers; but to regard someone’s wisdom, we must focus on the questions they ask.

A reminder that supporters receive access to series, extra topic break-downs at The Vault and can view the full archives, including online only updates to essays.

The Unpredictability of Fate

The brilliance of Sophocles, the sheer humanity of Aeschylus, the truth Euripides wouldn’t sacrifice for fame are trademarks of the value in culture we take for granted. My gratitude goes to all supporters for making this work possible.

Unlike his brother Epimetheus, whose name means ‘afterthought,’ Prometheus was always thinking ahead, particularly in relation to humanity’s needs.

Japan’s women could make or break entire industries by following what old-fashioned culture called ‘childish’ impulses. In 1990, Sanrio—the company behind Hello Kitty—had been deep in the red; by 2000, the firm was worth more than $1 billion.

Video is a trailer of the documentary of Italy’s largest Comic and Games Festival in Lucca.